Iran’s Untapped Soft Power Is Key to Its Success & Regional Stability

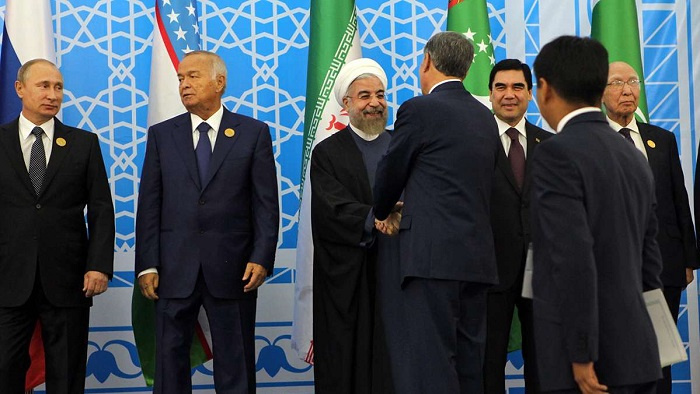

(President Rouhani in his visit to Tajikistan in September 2014 to attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Adel Bazyar/IRNA)

By: Sam Sasan Shoamanesh

Given the volatile state of the Middle East’s security landscape, increasing conflicts and regional tensions, Iran’s projection of military might is crucial to safeguarding the country’s national security. That said, in grand strategic terms, the nuclear deal, successfully negotiated two years prior, hints at the prospect of Iran’s untapped soft power being far more central to the country’s long-term sustainable success in the 21st century and greater stability of its neighbourhood. As the 13th-century Persian poet, Jalal ad- Din Muhammad Rumi, wrote:

“Raise your words, not voice. It is rain that grows flowers, not thunder.”

To be sure, in Iran’s conflict-ridden neighbourhood, the military instrument is a must to deter would-be aggressors. The devastating 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war taught Iranians this lesson at great cost in blood and national treasure. The menace of Daesh now increasingly focused on Iran and the pair of unprecedented callous terrorist attacks in Tehran in June of this year during the Holy Month of Ramadan only reinforce the need to bolster Iran’s intelligence and military capabilities to defend the country’s national security at a time of great regional uncertainty and peril.

Be that as it may, while critical, military assets, capabilities and advantage alone will not be sufficient to insulate Iran from the multitude of threat actors in its immediate neighbourhood and beyond. Iran’s military muscle, on its own, is neither capable of easing regional tensions nor winning the permanent admiration of Iran’s neighbours, building lasting alliances, or indeed helping Iran to leaven its relative isolation. As the Arab states of the Persian Gulf annually increase their military spending - largely in direct response to Iran’s military capabilities or perceived ‘Iranian threat’ - and with Tehran duly taking countermeasures, an acute security dilemma dictates the geopolitical logic of the region, fuelling instability and insecurity. As such, a parallel strategy that combines both the national defence capabilities of the country and soft power instruments of Iranian outreach ought to be adopted and employed, as required.

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (the Iran nuclear deal), concluded in July 2015 between Iran, the P5+1 and the EU, which received UN Security Council backing through Resolution 2231 and resulted in the lifting of economic sanctions on Iran, was not only a major success for Iranian diplomacy - a tour de force, without a doubt - but also boosted Iran’s soft-power credentials as a real player in the preservation of international peace and security (through peaceful means). Granted, the deal is increasingly being tested from the pressures and inclinations of the new administration in Washington, but the agreement, rightly, continues to benefit from the firm backing of European partners, Russia, China, and with few exceptions, the international community writ large. For our purposes, however, what is important to recognise is that the realisation of the deal itself has created a golden opportunity and the political space domestically - in particular, given the re-election of President Hassan Rouhani and a second term for his administration - for the government in Tehran to devise and implement a comprehensive strategy to project soft power in a way that both mitigates the regional security dilemma and serves the national advantage.

Since the founding of the Islamic Republic in 1979, Iran has relied heavily on its unique Shia character as the basis of its soft power to galvanize support from pockets of Shia populations in a Sunni-dominated Middle East and Central Asia. This policy has been deliberate and strategic, with clear ideological underpinnings. While it has had its successes - including Iran’s manifest clout today in Lebanon and Syria, or in Iraq after Saddam Hussein - its net effect is, by definition, limited in scope (and geography), constraining Tehran’s ability to generate long-term strategic dividends.

Indeed, relying on the Shia character for soft power projection is arguably inconsistent with the Constitution of the Islamic Republic, which requires the government to formulate its foreign policy on the basis of “fraternal commitment to all Muslims,” and its general policies “with a view to cultivating the friendship and unity of all Muslim peoples.” Moreover, just as it limits the full reach of Iran’s soft power beyond the Shia world, this approach also plays directly into sectarian divisions in the region; indeed, further entrenching alliances along sectarian lines. This is manifestly self-defeating, as it not only complicates Iran’s already difficult security environment, but also further isolates the country within its own geopolitical space. To be clear, the argument is not to abandon Iran’s Shia brethren but to adopt policies and postures which strengthen Iran’s ability to more effectively project positive influence beyond the confines of the ‘Shia’ world’, and position itself to more effectively advance the country’s national interests, and to lead by example by decreasing hostilities and attempt to stabilise its immediate neighbourhood.

Given Iran’s historical role, as well as its linguistic and cultural ties, in the ‘Greater Iran’ region - encompassing the Caucasus, West Asia, Central Asia, and stretching to parts of South Asia - the country has the potential to exert soft power to a ‘natural market’ - as it were - to advance its national interests. On this logic, the country can acquire greater influence regionally if, in addition to religious bonds, it skilfully invokes common historical, cultural, ethnic and linguistic ties with neighbouring states. Part of this push can involve, over time, a de facto reversal of some of the consequences of the treaties of Gulistan (1813) and Turkmenchay (1828) - that is, closing the artificial gap that these Russo-Persian war capitulations created between Iranians and their brethren from the Caucasus over the last two centuries.

President Rouhani’s carefully worded Nowruz message in March of last year is an example of such soft power in action. In a letter addressed to the heads of state of nine neighbouring countries celebrating this ancient new year tradition, he stated: “Nowruz is a festival of moderation and the most ancient dynamic tradition in our common history.” He went on to encourage “the countries of the Nowruz Zone to establish better and further relations with each other, in addition to friendship and reconciliation and create modern conditions for peaceful coexistence based on the historic nuclear agreement between Iran and P5+1 and the lifting of sanctions.” Much more such public diplomatic seduction is required.

Tehran should also capitalize on the momentum of the Iran nuclear deal as a trust building measure, to forge a network of states friendly to its interests, and to provide them with the necessary incentives to remain invested in such friendship through strategic partnerships, common projects, and financial cooperation. The tripartite agreement between Iran, India and Afghanistan, concluded this past May, to position the Iranian port of Chabahar as a transport and trade corridor is a case in point of a major national initiative that fits well into a larger soft-power push by Tehran. Such economic intermeshing may even lead to a common security regime over time, further integrating this triad. Other examples include efforts to revive the Silk Road trading route connecting Iran to China (through the Yiwu-Tehran train), the Iran-Azerbaijan agreement on trade and joint ventures to build hydroelectric plants and cooperation in respect of (increasingly scarce) water resources, as well as the International North-South Transport Corridor being explored between Russia, India, Iran and Central Asian states. The recent €2.5 billion deal on joint manufacturing of passenger and cargo railway wagons with Russia is, similarly, a welcome development.

When opportune, Tehran should also seek to extend similar projects to its Arab neighbours in the Persian Gulf, as well as to other states in the region and to other regional theatres - in full recognition of the fact that, with investment in political relationships and the necessary infrastructure, Iran could realistically become the region’s principal international transit hub.

Additionally, as I have observed in past, the Middle East is in dire need of a reengineering of the regional order through new institutions and structures that will enable it to better manage and avoid interstate conflict, and also to create opportunities for region- wide collaboration and integration. Of course, short of a comprehensive regional governance regime, Iran and Egypt were, in the 1970s, the first countries in the region to call for a Middle East Weapons of Mass Destruction Free Zone. Most recently, Iran served in the Vice-Presidency of the UN Conference to Negotiate a Legally Binding Instrument to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons, which resulted in a historic resolution being adopted last month banning nuclear weapons, with 122 UN member states voting in favour.

The Iran nuclear deal, then, arguably sits within this tradition of working toward a nuclear-free zone, and provides Tehran with an opportunity to champion the idea of a new regional security architecture based on the concept of common security, free of weapons of mass destruction, and anchored in a non-aggression pact.

If there is political will, different formulations towards a region-wide security framework are there for further exploration. One option would be to focus on membership expansion of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) to also include Iran and Iraq, on the basis of equal partnership and mutual respect with assurances of non-interference in the sovereignty and territorial integrity of signatory states. While today this may seem inconceivable or counterintuitive, in fact, such a development is a logical transformative step forward, capable of easing tensions amongst the Persian Gulf littoral states, altering the strategic calculus of this expanded corpus of GCC members in favour of common security and regional stability. Such an outcome can also act as a stepping stone towards wider regional cohesion.

This would, of course, be a long-term vision with undeniable challenges. However, in the interim, there is a low hanging fruit which can serve as a constructive trust building measure. For a number of years, I have argued that in the immediate term, a standing regional security forum to discuss issues of strategic concern, including the threat from Daesh, cross-border terrorism, and populations displaced by war and conflict must be established; that is, indigenously in the region, for the region, with the support of the UN and other helpful extra-regional actors as required and preferred.

On its merits and for a number of strategic imperatives at a time when the country’s security is increasingly under threat, including from Daesh and other external elements, Iran ought to lead and champion that cause. By doing so, Iran - and the region- could gain immeasurably. In particular, given that Iran finds itself facing intensified attempts at isolating the country, Tehran would be wise not to shy away in positioning itself conspicuously as a leader in the promotion of regional peace and stability. It is imperative that this is done sooner than later. To its credit, Tehran as of late has been signalling that it is open to assume such a role to promote precisely this idea, notably through declarations made by Iran’s Foreign Minister, Dr Mohammad Javad Zarif, most recently at an event convened by the European Council on Foreign Relations in Berlin. With tensions high in the region, not least amongst the Persian Gulf littoral states, Iran ought to back this proposal as a policy priority and make the necessary investments to ensure effective implementation.

Turning to cultural and people-to-people diplomacy, given Iran’s rich literary and artistic tradition, it stands to reason that the country’s filmmakers, actors, musicians, writers, poets, craftsmen, artists and athletes should be better known and celebrated in the world than they are today. They are worthy of funding and support in their own right, but for strategic purposes, they are a major source of untapped Iranian soft power in the region and internationally. The arts create intangible bonds of affection and affinity amongst peoples. You can’t hate what you admire; you can’t demonise what attracts. In that sense, art can serve as that crucial connecting bridge between peoples. Iran’s soft power will be all the more potent when its art power is on full display.

On this same logic, the promotion and mainstreaming of the Persian language abroad should be prioritized by strategists in Tehran. While some efforts are already underway in this regard, they need to be bolstered. Moreover, one of the other central pillars of Iran’s cultural diplomacy should also be continued commitment to inter-religious dialogue, building on past initiatives such as the Dialogue Among Civilizations, introduced by former Iranian president Mohammad Khatami.

An effective soft power strategy would also require the agents of this crucial work to be conversant in the tongues of their audience. Many countries around the world - and particularly some of the most strategically astute countries - already profit from the competitive advantage of competence in a multitude of tongues. The more languages the Iranian knows, the more effectively she or he can make an imprint beyond Iranian borders.

While preserving Persian as the official language and script of the country, it is in Iran’s interests to invest in a national languages strategy that will generate a critical mass of Iranians fluent not only in Persian but also Arabic (beyond grades six to 11), Turkish and other languages of the region. The English language should be taught earlier - ideally from the primary school level, as prescribed by countless pedagogical studies around the world. Scientific studies have indeed confirmed that learning additional languages at a young age has many benefits. In addition to ease in mastering the language itself, it promotes critical thinking, creativity, and overall strengthens cognitive ability. We might therefore eventually envisage an Iran where the average Iranian, in addition to Persian, also masters Arabic, Turkish, English and at least one other foreign tongue - say, French, Russian, Spanish, Chinese or German.

Iran’s ability to maximize its soft-power potential also surely rests on the quality of domestic governance - that is, its ability to keep its own house in order and ensure the general well-being and happiness of its citizens. Easing rigid state regulation of, and restrictions on, the private lives of Iranians, and taking steps to protect, and be seen to protect, human rights will be crucial not only for greater social cohesion and harmony - and ultimately, a stronger, united Iran - but also for Tehran’s ability to credibly project soft power abroad.

In this same vein, Iran’s multi-ethnic, linguistic and religious diversity should also be seen as an important part of the country’s soft-power toolbox. Iran should fully embrace this diversity not just for its intrinsic virtues, but also to ensure internal stability, and to demonstrate to the world that the country has an open and tolerant society. With a number of militant organizations, conceived on ethnic lines - and often supported by external elements - operating in Iran and posing a threat to national security and unity, Tehran’s countermeasures should include a targeted strategy of winning the hearts and minds of the country’s ethnic minorities in order to strengthen their loyalty to land and country. With Daesh and other external threats increasingly looking to infiltrate and recruit within Iran, the proposed policy is even more pressing.

It is conceded that Iran does not benefit from the safety buffer of geographical isolation. As such, concessions with respect to the country’s minorities can have a geopolitical dimension. That said, the status quo is not sustainable and will only embolden Iran’s enemies to sow the seeds of internal discord and disunity with serious risk for the country’s territorial integrity. Where legitimate, the government should properly address the grievances of these minorities. Intense and active consultation with minority groups – much more than seen to date – should form part of this strategy of redress. The socioeconomic health of ethnic minorities in the aftermath of the lifting of sanctions is one area in obvious need of attention by Tehran. So too is the opportunity to create new programmes to meaningfully celebrate Iran’s multi-ethnic and multilingual population - something anticipated by Articles 15 and 19 of the Iranian Constitution.

Diminishing internal discord in the country can only help Iran to more sustainably project influence beyond its borders, and also to parry disruptive forces and designs from outside the country. And while there is no substitute for Iran’s military capabilities, which clearly has its place in the country’s national security strategy, the soft power dimension is for now underplayed and underappreciated in Tehran. The Middle East is in dire need of toning down of tensions and reversing the perpetual security dilemma which condemns it to recurring conflicts. Iran is well placed to play that constructive leadership role, and it has every interest to do so. A proper national soft power strategy and push may be just the energy that the country and the region need to reckon with some of the vexing challenges of this early new century.

* Sam Sasan Shoamanesh is the Vice-President of the Institute for 21st Century Questions and Managing Editor of Global Brief magazine. This piece is an updated version of the original published by Global Brief magazine. *The views expressed are the author’s alone.