Iran’s Three Islands: Unchallenged Sovereignty

As scholars of international law have repeatedly emphasized, the principle of state sovereignty is as ancient as the state itself. According to the late Crawford, the prevailing modern conception of sovereignty entails the totality of internationally recognized rights and duties embodied within a territorially defined, independent entity known as the state. The notion of territorial sovereignty occupies a foundational position within international law. No state can exist without territory; consequently, the acquisition, control, and defense of territory remain central preoccupations of states worldwide. Many international disputes, whether explicit or implicit, revolve around territorial questions, underscoring the centrality of sovereignty in both international relations and legal theory. Sovereignty, alongside jurisdiction and territory, constitutes a defining characteristic of the state, distinguishing it from other subjects of international law. As Professor Shah insightfully notes, international law is fundamentally state-centric, and states themselves are predicated upon sovereignty, a concept that, internally, signifies the primacy of state institutions, and externally, affirms the state’s supremacy as a legal person. At the heart of this framework lies the critical link between sovereignty and territory: without territory, a legal entity cannot be recognized as a state.

Islands represent a particularly complex subset of territorial issues, and some contemporary scholarship refers to the emergence of a “legal age of islands.” The 1958 and 1982 United Nations Conventions on the Law of the Sea define an island as “a naturally formed land area, surrounded by water, which remains above water at high tide.” Notably, the definition does not require habitability. Islands, whether politically minor units or integral parts of a larger state, give rise to a host of legal questions: from fundamental territorial sovereignty to self-determination and human rights of their inhabitants. The assertion of sovereignty over islands, particularly as extensions of mainlands, represents one of the most contested areas in international law and politics. Recent disputes in the East and South China Seas, involving states such as China, Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan, exemplify the enduring salience of islands in contemporary geopolitics. These disputes have reached the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and various arbitral tribunals, reflecting both historical claims and contemporary strategic imperatives.

This note examines the principal legal mechanisms by which states acquire sovereignty over islands, drawing on ICJ judgments, arbitral awards, and historical legal doctrine. Building upon Professor Murphy’s 2016 lectures at The Hague Academy, five recognized modes of acquisition are identified: (1) discovery and occupation of terra nullius; (2) conquest or military occupation; (3) treaties or international agreements; (4) state succession; and (5) continuous and peaceful display of sovereignty. This study analyzes these modalities, alongside evidentiary requirements for establishing sovereign claims, while noting the limited contemporary relevance of conquest and the nuanced role of historical agreements.

1. Discovery and Occupation of Terra Nullius

The doctrine of terra nullius is deeply intertwined with European colonial expansion. As Fitzmaurice observes, it traces its origins to medieval legal thought, where unclaimed property (“res nullius”) could be acquired by the first possessor. Its earliest documented international application is in the 1885 dispute between Spain and the United States over Canton Island. Terra nullius, while obsolete as a practical doctrine today due to the scarcity of truly unoccupied territory, remains critical for historical claims of sovereignty over islands. Brownlie emphasizes that terra nullius refers to territory “without any sovereign authority,” and occupation served as a legal mechanism to establish sovereignty. The ICJ, in its advisory opinion on Western Sahara (1975) and in the Eastern Greenland case, reinforced that mere discovery without effective occupation does not confer complete sovereign rights a principle exemplified in the Palmes Island arbitration between the Netherlands and the United States.

2. Conquest or Military Occupation

Historically, conquest represented the acquisition of territory through armed force. Contemporary international law, however, strictly prohibits territorial acquisition through the threat or use of force, as codified in the Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928) and reaffirmed in the UN Charter. Conquest today is legally impermissible, except in cases of self-defense or as authorized by the Security Council. Nevertheless, historical instances of conquest may still inform the ICJ’s examination of prior sovereignty, provided sufficient documentary and practical evidence supports the claim.

3. International Agreements

International treaties or agreements remain perhaps the most transparent means of acquiring or confirming sovereignty. Treaties may cover broad territories or specific islands, as seen in the 1881 Argentina-Chile treaty or the 1891 Britain-Netherlands convention concerning Ligitan and Sipadan Islands. Crucially, the transferring state must possess valid sovereignty over the territory to confer it legitimately, a principle reflected in the Palmes Island case, where the ICJ invalidated Spain’s purported transfer to the United States due to the Netherlands’ prior claim. International law also recognizes implied consent and acquiescence; silence in the face of territorial assertion can constitute tacit approval, a principle repeatedly applied by the ICJ in island disputes such as Pedra Branca (Malaysia/Singapore, 2008) and in historical recognition of Iran’s sovereignty over the Greater and Lesser Tunbs.

4. State Succession

State succession entails the replacement of one state by another in responsibility for international relations concerning a given territory. This principle accommodates a variety of scenarios: dissolution of a state (e.g., the USSR in 1991), secession (e.g., South Sudan in 2011), decolonization, or annexation (e.g., Crimea in 2014). The ICJ recognizes that sovereignty over islands may transfer to a successor state, provided there is continuity of legal title. Evidence of uninterrupted sovereign administration is critical, as illustrated by the 2002 ICJ judgment on Ligitan and Sipadan, which rejected claims based solely on prior treaties when evidence of effective administration was absent.

Conclusion

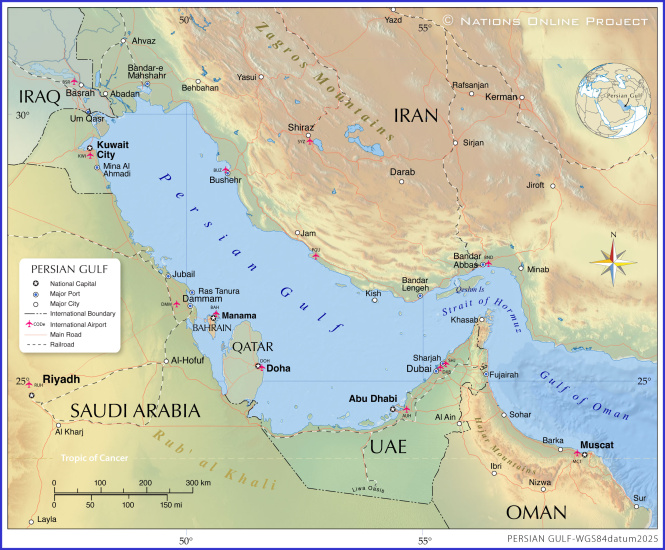

The law of island sovereignty represents a complex interplay of historical doctrine, treaty law, state practice, and judicial interpretation. The ICJ and arbitral tribunals have consistently emphasized the need for concrete acts of sovereignty, continuity of administration, and the relevance of historical claims within contemporary legal frameworks. For states such as Iran, the stakes are particularly high, given the geopolitical significance of islands in the Persian Gulf. Understanding the legal foundations and evidentiary standards for asserting sovereignty over islands is thus essential for both scholars and practitioners of international law. This note seeks to illuminate these principles, laying a foundation for deeper, more critical inquiry into one of the most contentious and strategically significant areas of international jurisprudence.

* MohammadMehdi Seyed Nasseri holds a PhD in Public International Law from Islamic Azad University, UAE Branch (Dubai). He is a researcher at the Center for Ethics and Law Studies, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran; and Lecturer in International Law at the University